I recently visited the JFK Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

I’m no history buff, nor am I particularly into admiring political figures of the past (or present, for that matter). But I must admit that the visit turned out quite fascinating on various levels.

This guy (John F. Kennedy, to be precise) clearly died way too soon. I picked up a few good quotations and a new-found respect for what he tried to do during his brief stint as POTUS.

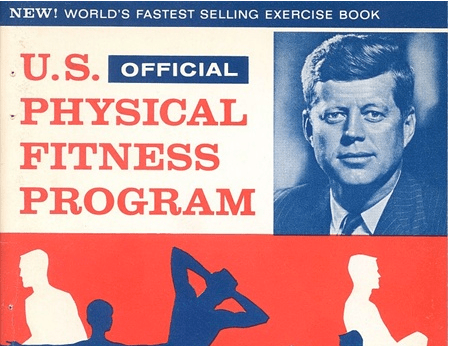

And I got one major surprise in the process, as the picture at the top of this post hints at.

You see, back in the early 1960s, people like JFK were already very concerned about the fitness level of Americans.

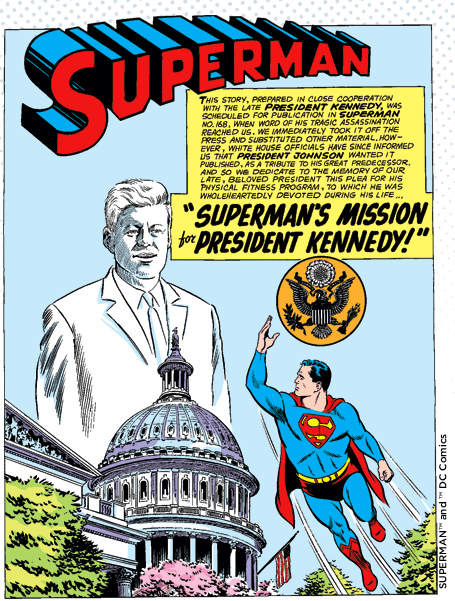

JFK re-launched a council on fitness early on in his presidency, and got a fitness program created and disseminated to schools in the US. Later on, he enlisted the help of the artist who was then drawing the Superman comics and asked him to create a special story in which Superman went on a mission to help kids get into better shape.

You could say that JFK was conspiring with a few other people to improve the fitness of Americans. That’s the kind of conspiracy that’s worth talking about.

Keep in mind that this was back in the early 1960s! Already then, there was unease about the fitness level of people, and of kids in particular…

Some things change, some things stay the same

Sadly, JFK died before the book was published, but his successor got the comics published, as you can see from the other image.

Did it work? Apparently not; the general population, and kids in particular, have been getting less fit, even though elite athletes have been getting better and records have been broken systematically. You could say a wider chasm has been growing in terms of fitness, even as people have been getting wider…

What’s really interesting, however, other than the fact that this was happening already over 50 years ago, is that very little has changed in terms of what is being recommended as regular physical activity. Except perhaps that infamous rope climbing thing (now we beat the crap out of floors with ropes). Sit-ups, pull-ups, push-ups, running, variations on those themes.

We also have a lot more evidence, scientific at that, about how much to move, and at what intensity. Guess what? We should be moving every day. That’s a no-brainer.

Why has it not worked?

That’s a fair question. Consider the simple fact that we’ve known for a long while how to maintain our bodies; we’ve just fallen short of finding better ways to get people moving when they are not.

Perhaps part of the problem is the lack of understanding of how to best promote fitness among kids. Standardized tests and competitions are not the way to go; measuring personal improvements based on heart rate and deployed effort is much better, as Dr. Ratey illustrates in his excellent book Spark, (and about which I provided a brief review a few days ago).

We tend to focus on providing logical, rational, scientific arguments, trying to convince everyone of the importance of moving. Unfortunately, that does not work. Our relationship to effort is one based on emotion, not rationality. That’s the real problem. Something even Superman couldn’t fix.

What can’t be denied is that the last 50 years have seen a continued rise of suburban lifestyles that almost make cars mandatory even as schools have been cutting their physical education courses and made free play practically illegal in schoolyards. Instead of walking everywhere and playing, sometimes rough, now kids are driven and made to behave all the time when in fact what they need is to learn to use their bodies in a fun way and spend energy.

In any case, let’s not forget that we’ve been struggling with this for a while, so a solution is not likely to be easy. But we’ve known for a while that we need to move more, on a daily basis. That remains the key.

Moving On

By the way, the council on fitness still exists, and every few years a new document is created, new guidelines are provided, and so on. It’s an ongoing battle. The documents are getting thicker, perhaps so they can be used for weight lifting some day. The site is there, though I have yet to find useful advice there.

Instead, we should all join the conspiracy directly and get moving. No thinking, no arguing, no rationalizing. Just moving.

Should you happen to be in the Boston area, I highly recommend a visit of the JFK Presidential Library and Museum. If you go, do as I did (and dragged my mom into doing with me): Walk from the nearest T stop instead of taking the bus. That way you’ll keep to the spirit of John “Fitness” Kennedy…

Images “borrowed” from the JFK Presidential Library and Museum Web site, which is visible to everyone, and that I highly recommend visiting to anyone in the Boston area (so please don’t sue me for having used them).